Born in the 1980s, shortly after house music emerged from the dance floors of Chicago, Detroit, and New York, hip-house was a shotgun marriage between two hot springs of black innovation. Ever since, it has served as shorthand for mixing the art of rapping with 4/4 dance rhythms. Its stock has risen and fallen precipitously over the decades. Yet it persists as a concept, with a reputation that lies somewhere between unalloyed club bliss and pop kitsch.

Debate persists on whether UK acts The Beatmasters and Cookie Crew’s 1987 sampladelic hit “Rok Da House,” or Chicago producer Fast Eddie’s 1988 track “Yo Yo Get Funky” (and his “Hip-House” cut) count as the first hip-house single. (For brevity’s sake, let’s focus on the American version of this sound.) Regardless of who got there first, it’s clear that someone would have mined the idea: rap producers like Doug Lazy, Marley Marl and DJ Mark the 45 King dabbled in house music, and funky hip-hop tracks like Eric B & Rakim’s “I Know You Got Soul” and Rob Base and DJ EZ Rock’s “It Takes Two” burned dance floors of all kinds.

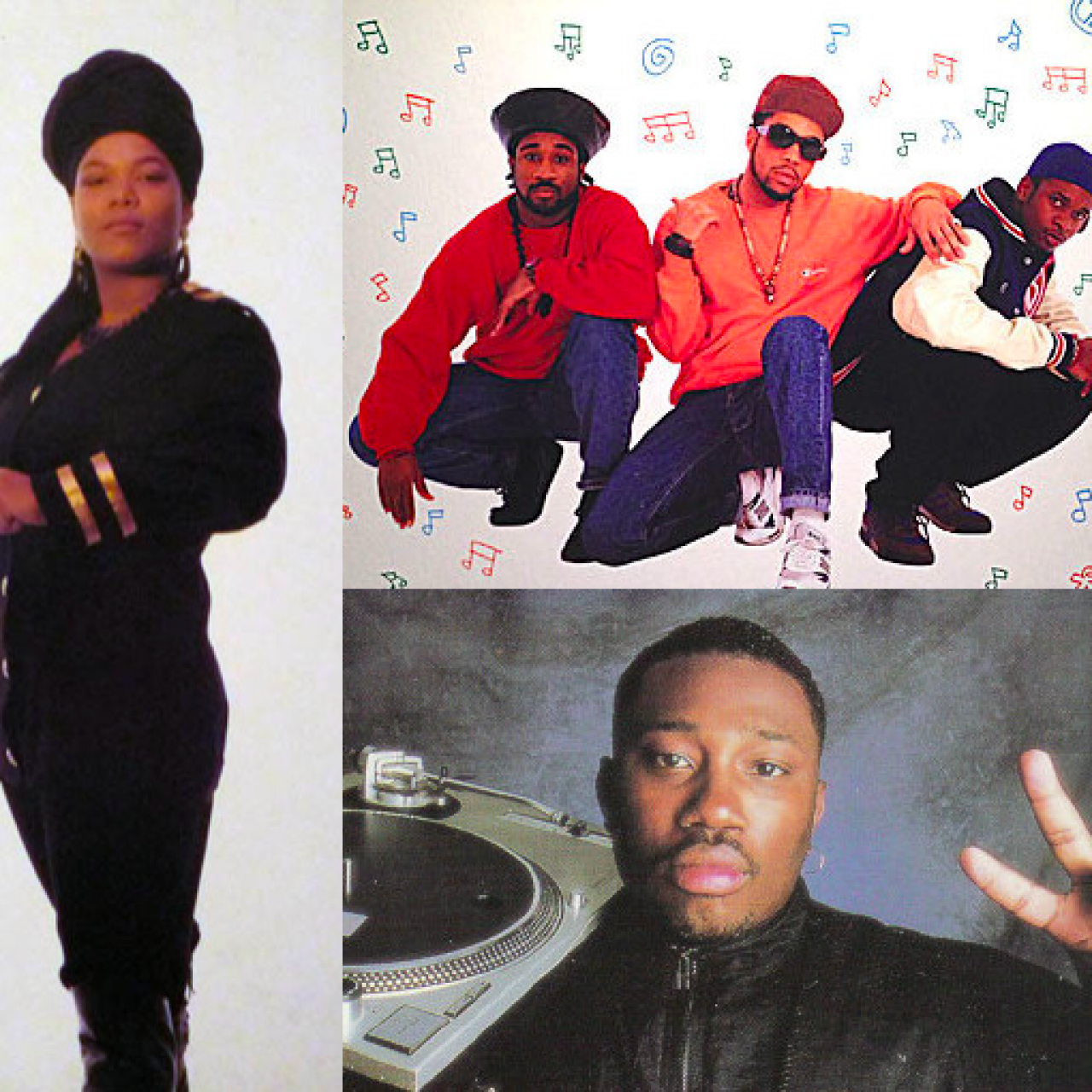

The most famous hip-house track of this era is Jungle Brothers’ “I’ll House You,” which blended Afrika Baby Bam and Mike G’s improvisations over an instrumental of Todd Terry’s “Can You Party.” The JBs are a wildly innovative trio whose music matched the Afrocentric optimism of that time more than any other, and they released two classic albums (as well as an underrated, misunderstood third album in J Beez wit the Remedy) before winding down in the early Aughts. But too many only know them as the fun-loving “I’ll House You” guys. Their fate is evocative of hip-house’s uncertain legacy.

Rap fans from the late 80s will remember how interwoven dance music was into the genre. EPMD, Queen Latifah and Intelligent Hoodlum (later known as Tragedy) made popular hip-house tracks. Others like Ultramagnetic MCs and 3rd Bass issued 12-inch house remixes. (MC Lyte’s “Lyte as a Rock (House Mix)” is a personal favorite.) They were part of a vibrant club mix: in addition to New Jack Swing and funk, MCs experimented with “house, bass and jazz” as Common later put it on “I Used to Love H.E.R.”

Hip-house began to fall out of favor in 1991. MCs recoiled at the increasing commercialization of the genre and club music, rightly or wrongly, was seen as an unnecessary compromise between pop gimmicks and hardcore aesthetics. Then there was the bigoted perception that house music was a queer and white European phenomenon. “Everybody was feeling hip house…until reality rap came. Then everybody wanted to be a gangsta because it looked cool,” says Tyree Cooper in Philip Mlynar’s 2016 oral history of hip-house for RBMA. “The gangsta rap was selling because [radio stations] exploited the culture of urban youth, exploited it to the fullest. Hip house and house music is a part of that, but they made it look like it was such a gay thing.”

By the mid-90s, R&B, funk, and mainstream dance-pop defined rap artists’ entrée into the club, not house. The hip-house sound has occasionally bubbled up ever since, but never with the mass popularity it inspired during hip-hop’s golden age.

Originally published on criticalminded.com. This post has been updated.

Humthrush.com will always be free to read and enjoy. If you like my work, leave a tip at Ko-fi.com/humthrush.