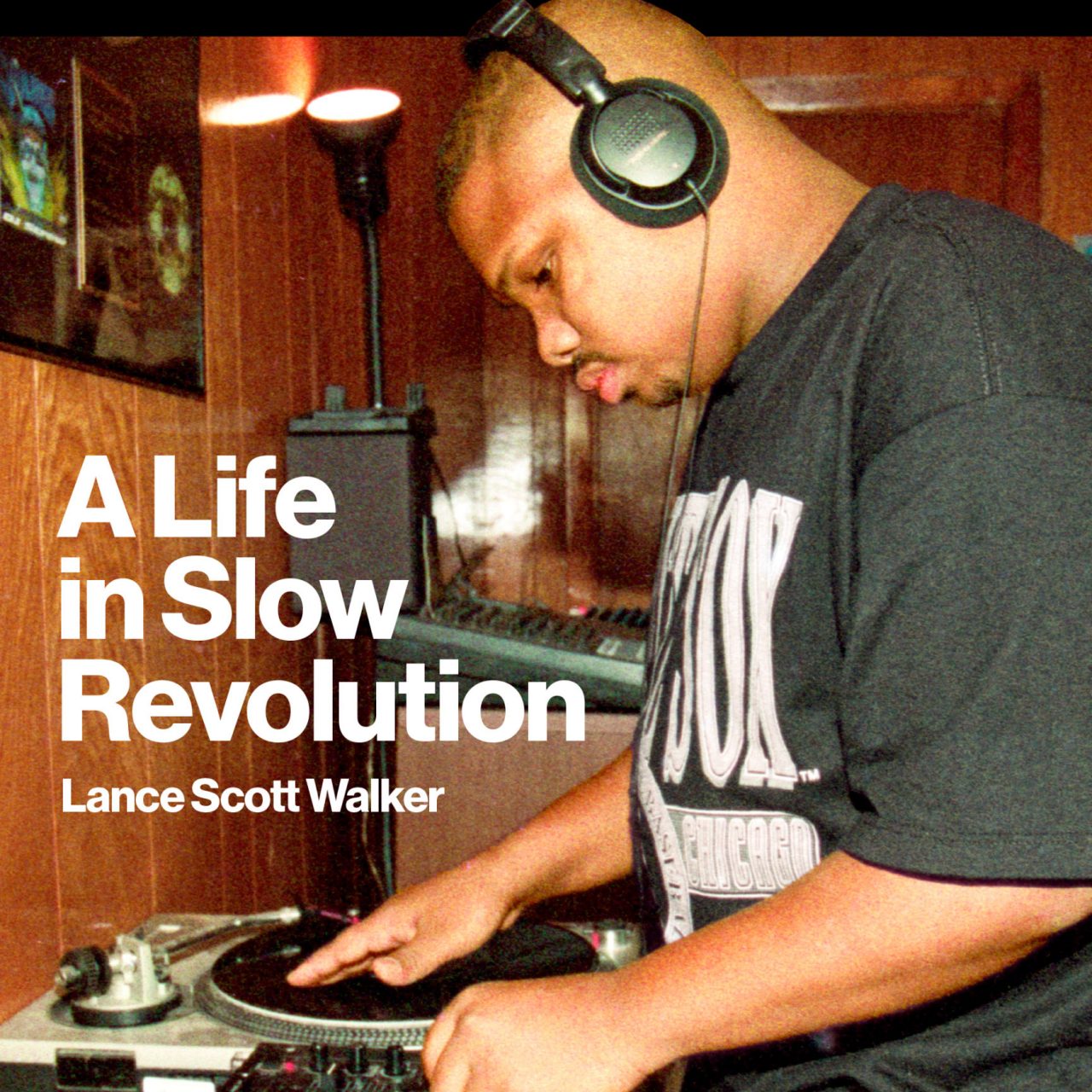

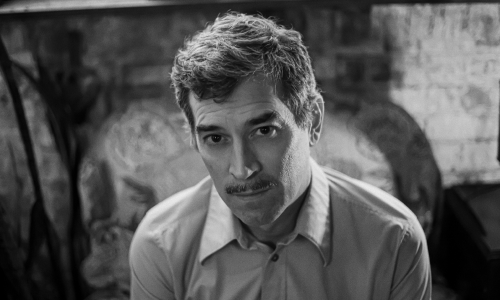

Earlier this year, Lance Scott Walker published DJ Screw: A Life in Slow Revolution. Its blend of oral history and third-person narrative offers the most complete portrait to date of a musician who has been widely mythologized since his untimely death in 2000 at the age of 29. A Texas native, Walker previously collaborated with photographer Peter Beste on 2013’s Houston Rap and 2014’s Houston Rap Tapes. In 2018, Walker republished and expanded the latter book as Houston Rap Tapes: An Oral History of Bayou City Hip-Hop.

One aspect of your book that others have pointed out is your mix of narrative and oral history. I’ve seen it used elsewhere, but instead of just using narrative to set up the long quotes, you seem use it as a parallel track, akin to a documentary with a narrator as well as talking heads. You explained in one interview that one of the reasons you did this is to center the Black community that nurtured Screw, not yourself as a white journalist. How did you strike a balance between the two — between giving the book structure while giving the voices equal weight? I imagine you had a surplus of material to utilize.

There was a surplus from which to draw, but striking the balance really had to do with taking the time to get a sense of the linear structure of Screw’s life and the major events or themes running through it, and then mining my interviews to look for an example of an interviewee talking about something relevant to that particular part of the timeline, to give it depth and a personal connection. All the while, I kept interviewing, and kept building from the information that came through in the transcriptions. I started the book off as a singular storyteller to get the reader oriented, but I very much wanted to “pass the mic,” as it were, to those who knew Screw and were close to him. The voices are the structure, because those folks I interviewed are recounting the stories of his life. Screw’s entire M.O. was to provide a platform for the people around him. I don’t know if I even realized it at first, but I was very much influenced by that and ended up following that approach over the years. In the end, my writing hopefully just provides connective tissue between the oral histories.

You reference an early Houston DJ, Darryl Scott, as well as Michael Price, who also used to slow down records. Did you have access to their mixes? Or did you rely on descriptions from people who had heard them?

I have never been able to get my hands on a Michael Price tape, so my knowledge of his sound only comes from what people have told me. As for Darryl Scott, I have known Darryl for years and visited Blast Records & Tapes many times before it closed. I have a collection of about two dozen D Scott mixtapes, so I’m deep into his catalog and influence on Screw. His touch on the turntables is a lot different from Screw’s but the influence comes from him, no doubt. I felt it was important to tell his story and that of the late Michael Price to show how their work informed Screw’s.

That leads to my next question: How much music did you listen to in preparation for this book? I’m not only referring to Screw’s tapes since you essentially tell the story of early Houston and Texas rap in this book.

I have been listening to Houston rap music since I was in high school in the late 80s, when we first heard the original Ghetto Boys down in Galveston. I moved to Houston in 1992, and living in Houston in the 90s, you couldn’t not hear DJ Screw around town. But over the last 18 or so years since I started working on this project, I have embarked on a deep dive. There has never been a point since 2004 where I wasn’t listening to music in studying for the books. Screw tapes are a big part of that, but I also let his support of local artists lead me down the path of their careers, how they were tied to him (or not) and how they pursued their work outside of his house. Houston’s hip-hop history is so interesting because you have very few people who move there to be a part of the scene, but you also have a scene where people stay put! Like the most famous rappers in Houston haven’t relocated to New York or L.A. They still live in the Bayou City, and that connects the generations in a really organic way. The network between the artists in Houston is thick, and the independent nature of its various hip-hop scenes means that even if you’re like me and you try to listen to everything you can, find everything you can, you’ll still never run out of things you haven’t yet heard.

Can you explain what the Northside-Southside rivalry is about? You mentioned it in a few places, but I didn’t get a sense of the scale of it. That’s understandable: I’m not from Texas, so I don’t know the history as intimately as, say, the Crip-Blood rivalry in California.

It was a sort of Crip-Blood rivalry, but nowhere near as violent or widespread. I have been told numerous times that it started over a set of rims, but have never been able to get the actual story. What I can say is that though this is spoken about in the context of hip-hop, it wasn’t really the artists who were throwing gas on the fire. Things did flare up, some people did lose their lives in altercations, and lots of things were said on Screw tapes (again, not really by the artists you know by name) over the years, but it was nothing compared to actual gang violence you might read about happening elsewhere. The beef largely ran its course by the turn of the century, and Southsiders and Northsiders started making records together — first E.S.G. and Slim Thug, and then Lil’ Keke and Slim Thug, and after that the gates opened up. Everybody works together now.

At certain points, you mention the criticism that Screw’s music was “devil worshipper” and “drug” music. How widespread was this impression? Did he have church folks speaking out against him?

In a 1999 [XXL magazine] interview with Daika Bray, Screw did refer to people saying that his music dragging indicated devil worship, but I never ran into any other instances of anyone saying that. This may have been something that [was] confided privately to him, or by someone who had encountered that feedback, but I don’t have reason to believe that was a common sentiment. However, lots of folks definitely made the connection to drugs. After he died, the media went wild and ran with it, so that association was pretty well locked in after 2000, but I wouldn’t say that was nearly as much the case before he passed. DJ Screw was beloved by multiple generations of Texans during his lifetime. Besides some objection from record labels of Screw using their songs on his tapes at first, I don’t know of anyone speaking out against him about anything!

You mention a scene where Screw’s team meets with an Epic Records executive. Whatever became of that meeting? Were there other labels trying to sign him? Why didn’t that work out? I know that the major label land rush on Texas acts (Big Moe, Lil Flip, etc.) had only just begun when Screw passed.

He wasn’t looking to sign with anyone, so nothing ever got off the ground. The major label rush on Houston acts largely happened after Screw died, and more so even after Southwest Wholesale — a major local P&D house — went out of business in early 2003. With Southwest, Houston really had a system where they didn’t have to look outside of the region to make money off their music. Everything was pressed up and distributed locally/regionally, and artists got paid. Once that caved, deals started getting made between major labels and Houston artists/labels, and of course everything exploded in 2005. Would that trajectory have happened the same way if Screw had lived? No telling, but I can say it likely wouldn’t have happened at all if not for the foundation he put down.

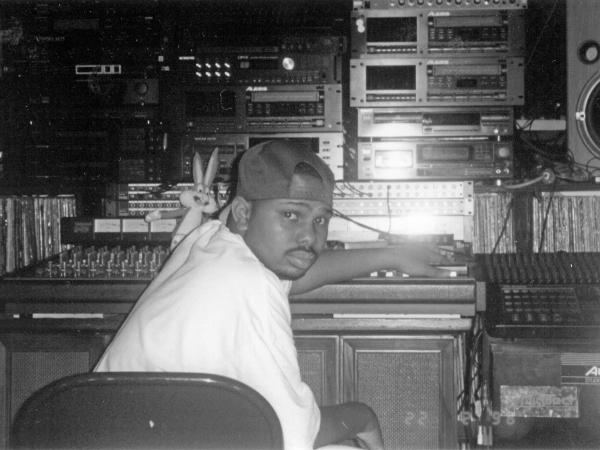

One thing I love about Screw’s tapes is how he could transform a song into something nearly unrecognizable, not only by “screwing” it, but also by adding turntable effects and flipping back-and-forth and repeating verses. A prime example is how he transforms Point Blank’s “After I Die” into an eight-minute epic. Can you speak on the process of how he achieved this? I’m particularly amazed at how he layered all those effects over the original tracks.

For the sessions that produced that track, for the album All Screwed Up, Screw was recording in an actual studio, with access to four turntables and acapellas/instrumentals from the label, as it was a Bigtyme Recordz project. So he had more latitude than usual, but I think that also illustrates his genius. It shows you how much he was doing with very little technology for the most part. That was a rare exception there, where he had that much gear at his disposal, and every time he got into a big studio, the engineers were blown away by the fact that he already knew what to do, what he wanted, and how to take advantage of gear he’d only ever seen or heard about, but not owned and maybe had never touched. But once he got that chance, he wasted no time, and worked in the studio like he did at his house — for as long as he could keep everybody else awake. And while you can hear the difference, it also shows just how good he was with songs he wasn’t even taking apart — songs he didn’t have the acapellas and instrumentals for, records he only had one copy of. He practiced all the time, like literally worked at the turntables for so many hours, so many days, such a huge portion of his waking hours, that when he got the opportunity to work within other possibilities — whether that be in a studio or just with the gear he was using — he figured it out quickly. He adapted. I think his early days of DJ’ing in clubs had a part to do with that, too. There was a point where he became really professional with what he was doing, and that allowed him to pounce on the possibilities of new setups like that to experiment like he did with “After I Die,” just dragging that thing off into outer space for so many minutes, stretching out the verses, working in musical parts you’ll hear sprinkled through other sections of the album, basslines and trumpets coming in and out. He had an incredible focus on what parts he had going on each of the four turntables, and how they all needed to be spinning, and when the needles needed to drop where. If he didn’t like the way he cut something together, he went back and redid it. Nothing was by accident.

Finally, your book ends by chronicling how mainstream pop culture absorbed Screw’s innovations. It reminds me of Dan Charnas’ Dilla Time, which spends a lot of time on the same “life after death” phenomenon. In your opinion, how much does this process elevate — and distort — Screw’s legacy? You touched on this a bit when you feature several folks complaining that only Screw can make a “chopped and screwed” mix.

It both elevates and distorts, but I also come from a part of the country where every soda is called a “coke,” so I get it. The canon authority would be the Screwed Up Click, and DJ Screw himself, who collectively said over and over that nothing is a Screw tape, Screwed, or Chopped & Screwed unless DJ Screw made it. Now nobody really calls their tapes Screw tapes, but I have heard plenty of people referring to contemporary music as “Screwed,” or “Chopped & Screwed.” My feeling is that the former, Screwed, is a bit more open-ended seeing as Michael Price’s process was also called “screwing” the music, but “Chopped & Screwed” certainly belongs to DJ Screw himself. In my work I refer to everything else as “Slowed and Chopped,” which is accurate seeing as it doesn’t involve his name. Hopefully the book will square that up. I will say that I think it’s great that other DJs have adopted Screw’s techniques and put their own touch on it. I think that definitely elevates the art form, and shows that it’s about all personal expression. It always has been.

Originally published on criticalminded.com. This post has been updated.

Humthrush.com will always be free to read and enjoy. If you like my work, leave a tip at Ko-fi.com/humthrush.