“We are the future! You are the past!” proclaimed Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic Force on “Looking for the Perfect Beat.” Produced by Arthur Baker, with keyboards by John Robie, the seven-minute whirlwind of electro keyboards, percussive bass and turntable cuts may be the Bronx crew’s finest moment. Released in the first week of 1983, it encapsulated much of the nascent dance world’s shift towards florid electro kingdoms suitable for arcade-obsessed kids and break-dance fanatics.

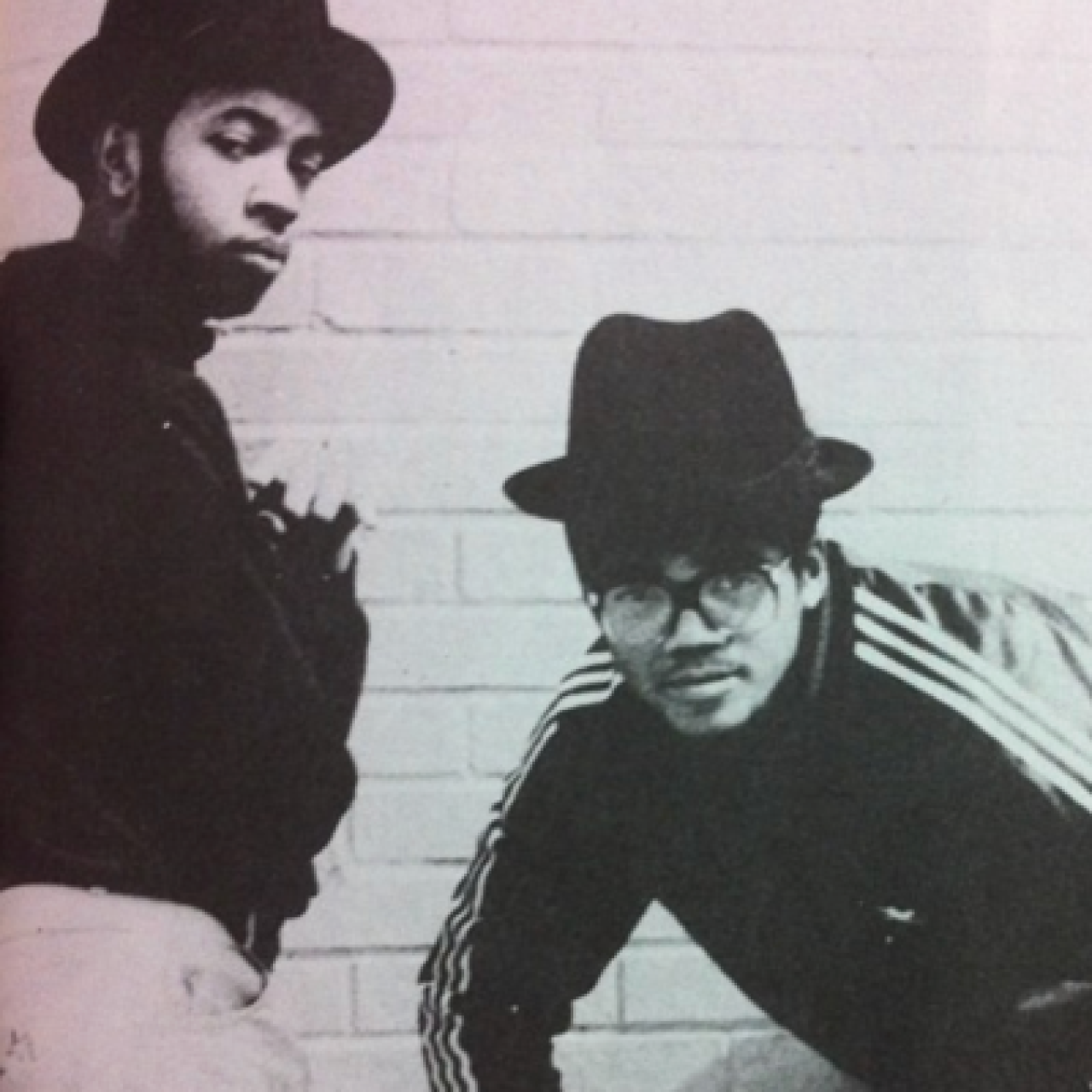

A few months later, Run-D.M.C. issued their debut single, “It’s Like That” b/w “Sucker M.C.’s (Krush-Groove 1).” The Hollis, Queens trio were little known outside their familial connection to Kurtis Blow’s manager, entrepreneur Russell Simmons. Simmons’ younger brother Joseph “DJ Run” Simmons had spent his teen years DJ’ng for Kurtis. Run and his high-school friends Darryl “D.M.C.” McDaniels and Jam Master Jay had only begun giving concert performances in 1982. Yet they, not Bambaataa, proved to be the future.

Run-D.M.C. were the leading edge of what would soon be called the “new school,” the first generation of artists to follow the pioneers who created hip-hop culture. If Bambaataa as well as Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five signaled their growing fame with P-Funk robes and Rick James-styled leather garb, then Run-D.M.C. modeled themselves after the brusque cool of street hustlers, sticking to leather jackets, gold chains, and Adidas sneakers. Still, much of their vocal approach was directly influenced by Cold Crush Brothers, who made halting inroads into the record industry with “Punk Rock Rap.”

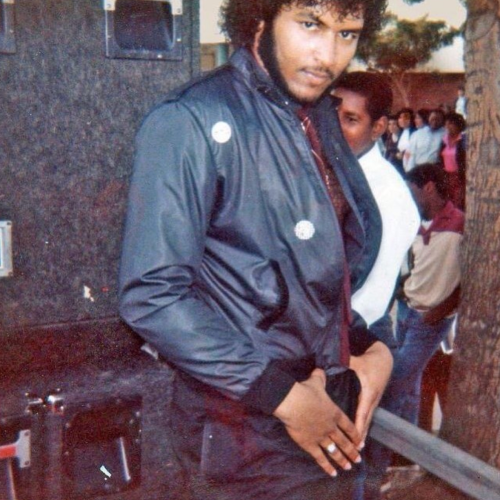

Meanwhile, a punk-rock band from Brooklyn, Beastie Boys, issued a spoof, “Cooky Puss,” only to realize that rap, not the increasingly rigid hardcore scene, would become the apotheosis of youthful resistance in the years to come. Less celebrated yet just as important were the increasing presence of mobile DJ party crews across the country. L.A. talents like rappers Ice-T and Rodney O, DJ/producer Chris “The Glove” Taylor, and producer/DJ/vocalist Egyptian Lover didn’t rate a mention in the first edition of The Rap Attack: African Jive to New York Hip-Hop, which British journalist David Toop published in 1984. Neither did “Pretty Tony” Butler, whose productions for Miami electro-pop acts like Freestyle and Debbie Deb resonated in hip-hop scenes not yet strictly defined by rap.

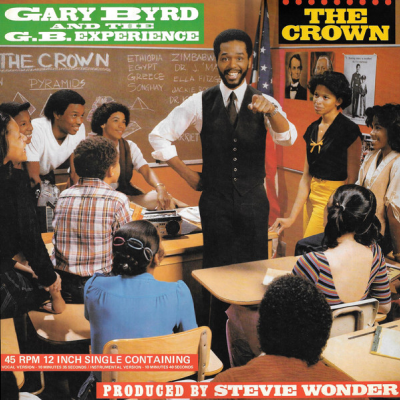

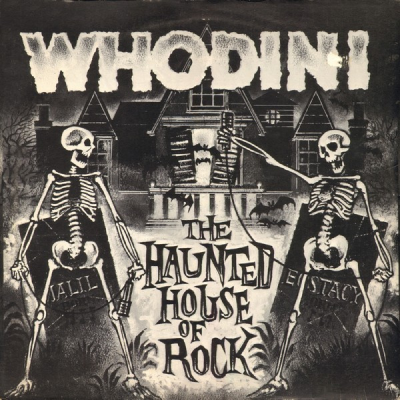

All this unfolded in an environment that continued to dismiss hip-hop as a passing fad. Despite backing from newly formed major label subsidiary Jive Records, Whodini’s self-titled debut album performed better in Europe, where singles like “The Haunted House of Rock” charted in several countries. Former Black Power activist turned radio jock Gary Byrd’s “The Crown” boasted production and hooks from Stevie Wonder as well as backing vocals by Teena Marie, Syreeta Wright, and Andrae Crouch. It became a hit overseas while white American radio programmers ignored it. And while hip-hop’s cross-pollination with dance music inspired British producers like the Art of Noise to assemble ingenious, crisply edited instrumentals like “Beat Box,” the U.S. communicated its disdain by elevating Rodney Dangerfield’s lovably dumb parody, “Rappin’ Rodney.”

Despite breakthrough crossover acts like Michael Jackson and Prince finally cracking heavy rotation on MTV, American pop remained racially segregated. Hip New York journalists may have begun calling Bambaataa a visionary who flaunted his ideas through techno-funk side projects like Shango and Time Zone. But few asked why one of the hottest Black artists in the country couldn’t get more airplay despite selling hundreds of thousands of 12-inch singles. Meanwhile, Black radio executives restricted the genre’s reach to late-night and weekend mix shows, a format where DJs like Whodini mentor Mr. Magic and his talented protégé Marley Marl, the Awesome Two, and “Zulu Beats” members like DJ Red Alert and Jazzy Jay held sway.

A few industry veterans like jazz keyboardist Herbie Hancock embraced hip-hop’s potential. A fancifully bizarre clip from British videographers Godley & Creme turned “Rockit,” Hancock’s collaboration with Grand Mixer D.st and Bill Laswell’s ever-evolving collective Material, into an Grammy-winning example of how Black musicians felt free to experiment with a genre not yet defined by expectations. But as the likes of Con Funk Shun, Twennynine with Lenny White, and Chocolate Milk peppered their records with funky verses, it wasn’t always clear if they were paying sincere homage or simply patronizing young people who increasingly embraced the art form. To a world slowly immersing itself in the turbo-charged possibilities of Silicon Valley technology, Reaganomics, Thatcherism, and cold-war annihilation, hip-hop seemed likely to melt into underground nightlife: a plaything for arty iconoclasts like Jean-Michel Basquiat, funk spicing for George Clinton a.k.a. “Pretty C” and Prince, a fad for teens like New Edition, and a joke for parodists like Blowfly and Divine.

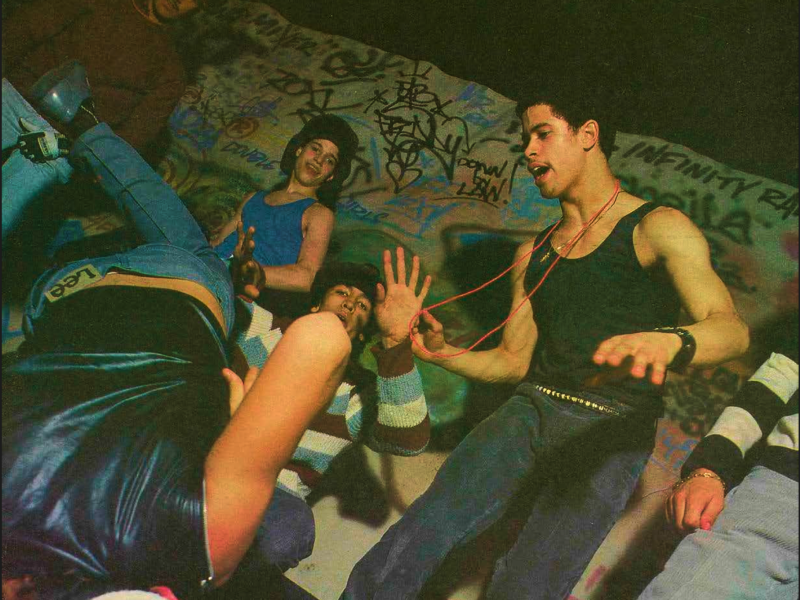

When Charlie Ahearn released his groundbreaking independent film Wild Style, he illustrated a hip-hop scene richly populated with aerosol artists, dancers, DJs, rappers, and fans who express their creativity through eye-catching fashion and style. The movie’s protagonists — real-life scenesters like Fab 5 Freddy, Lee Quiñones, Lady Pink, Patti Astor, Cold Crush Brothers, and Busy Bee — navigated modest commercial attention while attempting to maintain artistic integrity and avoid selling themselves out. Today, Wild Style not only seems like definitive proof of how a generation of youth took hip-hop very seriously, but also how they would grow into a global movement of acolytes who cultivate it with loving care. Still, Ahearn’s thesis may be more obvious now than 40 years ago.

Run-D.M.C.’s debut single, produced by Larry Smith’s Orange Krush team, epitomized the tension between what rap music was and what it could become. The group pushed Smith to make the tracks as raw as possible, without the electronic elements that typified Black pop in that era. “It’s Like That,” a declamatory message rap with jarring electro keyboards, split the difference. But “Sucker M.C.’s,” where DJ Run and D.M.C. floated over skittering, bare-bones percussion that accented their deftly rendered rhymes, pushed their hardcore aesthetic to extremes by avoiding any trace of melody.

The electro tunefulness of “It’s Like That” and the beat-box minimalism of “Sucker M.C.’s” represented two paths the genre could take. In 1983, no one knew which style an emerging generation of fans would prefer.

The 60 Best Rap Singles of 1983

- Afrika Bambaataa & Soul Sonic Force, “Looking for the Perfect Beat” (Tommy Boy)

- Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic Force, “Renegades of Funk!” (Tommy Boy)

- Art of Noise, Into Battle with the Art of Noise: “Beat Box” / “Moments in Love” (ZZT)

- The B Boys, “Two, Three, Break” (Vintertainment)

- The B Boys, “Rock the House” / “Cuttin’ Herbie” (Vintertainment)

- Beastie Boys, “Cooky Puss” (Rat Cage Records)

- Bernard Wright, “Funky Beat” (Arista)

- Captain Rapp, “Bad Times (I Can’t Stand It)” (Becket Records)

- Captain Rock, “The Return of Capt. Rock” (NIA)

- Caution Crew, “Rhythm Rock (I Like It)” (Galleon Records)

- The Cold Crush Brothers, “Punk Rock Rap” (Tuff City / CBS Associated Records)

- Crash Crew, “On the Radio” (Bay City Records)

- Dimples D., “Sucker D.J.’s (I Will Survive)” (Partytime)

- Disco Four, “We’re at the Party” (Profile)

- Fantasy Three, “It’s Your Rock” (Specific Records)

- Fantasy Three, “Biters in the City” (C.C.L. Records Inc.)

- The Fearless Four, “Problems of the World” (Elektra)

- G-Force feat. Ronnie Gee & Captain Cee, “Feel the Force” (SMI)

- Gary Byrd and the G.B. Experience, “The Crown” (Wondirection)

- Gigolette, “Games Females Play” (The Fever)

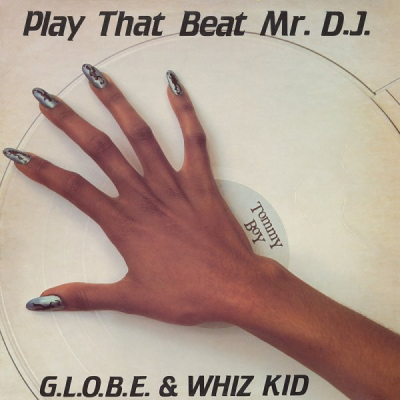

- G.L.O.B.E. & Whiz Kid, “Play That Beat Mr. D.J.” (Tommy Boy)

- Grand Master Caz and Chris Stein, “Wild Style Rap” (Animal Records)

- Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five, “New York New York” (Sugar Hill)

- Grandmaster & Melle Mel, “White Lines (Don’t Don’t Do It)” (Sugar Hill)

- Herbie Hancock, “Rockit” (Columbia)

- I.R.T. (Interior Rhythm Team), “Watch the Closing Doors!” (RCA Victor)

- Ice “T”, “The Coldest Rap” (Saturn Records)

- The Jazzie Ladies, “Blowin’ Your Mind” (Prelude Records)

- Jimmy Spicer, “Money (Dollar Bill Y’all)” (Spring Records)

- K-9 Corp (Featuring Pretty C), “Dog Talk” (Capitol Records)

- Kevie Kev (Waterbed Kev), “All Night Long (Waterbed)” (Sugar Hill)

- Kurtis Blow, “Party Time” (Mercury)

- “Love Bug” Starski, “You’ve Gotta Believe” / “Starski Live at the Disco Fever” (The Fever Records)

- Malcolm McLaren, “Hobo Scratch (She’s Looking Like a Hobo)” (Island)

- Malcolm McLaren, “World’s Famous” (Island)

- Malcolm X, “No Sell Out” (Tommy Boy)

- Newcleus featuring Cozmo and the Jam-On Production Crew, “Jam-On Revenge” (Mayhew Records)

- Prince, “Irresistible Bitch” (Warner Bros.)

- Pumpkin, “King of the Beat” (Profile)

- The Radio Crew, Breaking and Entering (Rainbow Television Workshop)

- The Rake, “Street Justice” (Profile)

- Rammelzee versus K-Rob, “Beat Bop” (Tartown Record Co.)

- Rickey G. & The Everloving Five, “To the Max” (Capo)

- Rock Master Scott & The Dynamic 3, “It’s Life (You Gotta Think Twice)” (Reality Records)

- The Rocksteady Crew, “(Hey You) The Rocksteady Crew” (Atlantic)

- Run-D.M.C., “It’s Like That” / “Sucker M.C.’s (Krush-Groove 1)” (Profile)

- Run-D.M.C., “Hard Times” / “Jam-Master Jay” (Profile)

- Shango, “Zulu Groove” (Celluloid)

- Solo Sounds, “We’re Chilly” (SnJ Records)

- Spoonie Gee, “The Big Beat” (Tuff City / CBS Associated Records)

- Spyder-D, “Smerphies Dance” (Telestar Cassettes)

- Sweet G, “Games People Play” (The Fever)

- Treacherous Three, “Action” (Sugar Hill)

- Tski Valley, “Cut It Up” (Grand Groove Records)

- Twilight 22, “Electric Kingdom” (Vanguard)

- Two Sisters, “B-Boys Beware” (Sugarscoop)

- Uncle Jamms Army, “Dial-A-Freak” (Freak Beat Records)

- West Street Mob, “Break Dance-Electric Boogie” (Sugar Hill)

- Whodini, “The Haunted House of Rock” (Jive)

- Whodini, “Rap Machine” (Jive)

Run-D.M.C. featured photo by Patricia Becker. Published in The Rap Attack, 1984.

Photo of Egyptian Lover during an Uncle Jamm’s Army event at Kennedy High School in Granada Hills, CA taken from his Instagram account.

Photo of Crazy Legs and the Rock Steady Crew at the Roxy by Red Saunders. Published in Rolling Stone, May 26, 1983.

Vinyl images taken from Discogs.

Read More: Best Rap Singles: Class of 1983

Humthrush.com will always be free to read and enjoy. If you like my work, leave a tip at Ko-fi.com/humthrush.