In 1982, a handful of rap records justified the faith of enthusiasts who had begun referring to hip-hop as the new punk rock.

The previous year, New York journalists, cultural workers, and industry gatekeepers became increasingly aware that hip-hop was more than just a “Rapper’s Delight” gimmick. In “Rappin’ to the Beat,” TV news magazine 20/20 explored the burgeoning scene, spotlighting Kurtis Blow as well as the Sugar Hill Records roster and local breakdancers. New Wave groups like Was (Not Was), The Clash, and Tom Tom Club tried their hand at harmlessly quirky rhymes. On Blondie’s Billboard number-one hit “Rapture,” lead singer Debbie Harry spun a ridiculously Godzilla-sized verse about “eating cars” while shouting out Fab 5 Freddy and Grandmaster Flash. Meanwhile, rising art star Jean-Michel “Samo” Basquiat appeared in the music video. When Blondie appeared on Saturday Night Live, they invited Funky Four + 1 More to perform, marking the first time a hip-hop group performed on national television.

Meanwhile, the 12-inch recordings themselves seemed stuck in the same “Rapper’s Delight” mode of party-rocking disco-funk, with Flash’s pioneering turntablism routine “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel” as an exception.

Afrika Bambaataa & the Soulsonic Force’s “Planet Rock” shook up the genre overnight. A collaboration between Bambaataa, rappers Pow Wow, G.L.O.B.E., and Mr. Biggs; keyboard programmer John Robie, producer Arthur Baker, and backing vocalists Planet Patrol, the song arrived in the spring of 1982 as a futuristic whirl. It not only built on the nascent genre’s predilection for interpolations, referencing Kraftwerk’s “Numbers” and “Trans-Europe Express” as well as Captain Sky’s “Super Sporm” and Babe Ruth’s “The Mexican.” It also anticipated hip-hop’s future as a wholly electronic product.

While “Planet Rock” injected hip-hop with much-needed sonic innovation, Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five’s “The Message” brought thematic focus. Contrary to what many critics believed, it wasn’t the first “socially conscious” rap song: the fact that Melle Mel’s final verse is a slowed-down reprise of his lyrics from the 1979 single “Superappin’” debunks that myth. In fact, Melle Mel is the only person from the group who performs on the song, which was conceived and mostly written by Sugar Hill in-house musician Duke Bootee. But thanks to Clifton “Jiggs” Chase and Ed Fletcher’s keyboard-driven funk and loping, post-disco groove, Bootee’s Last Poets-inspired lyrics about deprivation and squalor in New York City come into sharp focus. The song has a funky toughness that rappers have referenced ever since, from Ice Cube’s 1993 hit “Check Yo Self (Remix)” to Coi Leray’s 2022 single “Players.”

As noted by Questlove in his memoir Mo’ Meta Blues, hip-hop trends can shift so abruptly that it feels as if life has changed overnight. One year, dudes are rocking velour sweaters; the next year, they’re wearing studded leather jackets. These impressions, which were especially pronounced in the first two decades or so of the culture’s existence, may be as much illusion as fact. After all, the electronic bounce of Treacherous Three’s 1981 single “Feel the Heartbeat” as well as other post-disco raps arguably prefaced the arrival of “Planet Rock.”

Still, it must have felt like everything flipped with “Planet Rock.” By the fall, dance floors were filled with homage to sci-fi arcana and surreal cartoon trends, from Steven Spielberg’s Hollywood blockbuster E.T. the Extra Terrestrial to newly imported Dutch cartoon and Saturday-morning TV smash The Smurfs. Meanwhile, connections between the Boogie Down Bronx and the Manhattan culture industry strengthened. Rock nightclubs like Club Negril booked rap acts. Dance imprints like Tommy Boy and Celluloid joined traditional rap powerhouses in pressing the hottest tracks. The result was a melding of post-punk edge, post-disco groove and party-rocking energy. Singles like Nairobi and the Awesome Foursome’s “Funky Soul Makossa” celebrated the new downtown energy. More would come.

For a time after “Rapper’s Delight,” a hip-hop freak could reasonably claim that the best music wasn’t found on the stiffly formal 12-inch novelties that followed in its wake, but on the dubbed cassette tapes of live performances that circulated throughout the city. Cold Crush Brothers vs. Fantastic Romantic Five, Busy Bee vs. Kool Moe Dee, the Bozo Meko bootlegs of Grandmaster Flash: these were the true reflections of hip-hop as a burgeoning youth movement.

Thanks to the miserly business practices of producers and label executives, rap 12-inches wouldn’t be lucrative for musicians for the foreseeable future. But they could project an act’s name far beyond the five boroughs, and that put pressure on the kings of the live hip-hop circuit to finally get in the studio, lousy circumstances or not. No one represented that quandary better than Cold Crush Brothers. When the Bronx superstars finally released the 12-inch single “Weekend,” it sounded half-hearted, a facsimile of their dynamic concert material. Cold Crush would fare a little better in the months to come, when frequent performances in downtown Manhattan inspired them to adopt a “punk rock and rap” persona.

Meanwhile, scenes outside of New York were beginning to mature, albeit slowly. In Los Angeles, producer Jerry “Duffy” Hooks III continued to nurture his Rappers Rapp Co. imprint with the Rappers Rapp Group. In Britain, Malcolm McLaren recruited WHBI-FM personality jocks the World Famous Supreme Team to collaborate on “Buffalo Gals,” a single which incorporated the clipped edits of Trevor Horn’s The Art of Noise. Horn and co.’s style would eventually wield enormous influence on rap production, with the likes of Marley Marl and Mannie Fresh citing them as an influence.

It had been nearly ten years since Kool Herc introduced the “merry-go-round” during his sister Cindy Campbell’s “Back to School Jam” at a rec center in South Bronx. By 1982, the nascent hip-hop genre was finally growing out of its highly localized, prepubescent phase. The world awaited.

There is one final, troubling note on 1982. It would be easier to simply celebrate Afrika Bambaataa’s status as the year’s unquestionable MVP than mention the recent sexual-misconduct accusations that have damaged his legacy. Those heartbreaking allegations can’t dim the massive achievement that “Planet Rock” represents. An editor and colleague of mine, Charles Aaron, reminded me of this when we worked on a project together. When I wondered if Bambaataa’s reputation should disqualify “Planet Rock” from a list of the greatest pop songs, he responded that Bambaataa was only one of several people who helped create that classic. Arthur Baker, John Robie, Mr. Biggs, Pow Wow, G.L.O.B.E., Planet Patrol: “Planet Rock” belongs to all of them.

As I wrote two years ago in my survey of the best rap singles of 1980, there is so much that may never be known about the early years of the rap industry. Some of the mystery, like Bambaataa’s famed wariness over publicly revealing his birth date, is intentional. Other important moments, like the circumstances surrounding the SD’s and Shelly Richard’s single “Watch the Clock,” which may be the first rap single out of New Orleans, remain difficult to parse due to benign neglect and a lack of scholarship.

A search for details about the participants who made these songs, their recording conditions, and their communities may lead to painful truths. Uncovering all of this history, no matter how good or bad, can help us understand the development of the most important sound of the last five decades.

The 50 Best Rap Singles of 1982

- Afrika Bambaataa & The Soul Sonic Force, “Planet Rock” (Tommy Boy)

- Blondie & Freddie, “Yuletide Throw Down” (Flexipop)

- Busy Bee, “Making Cash Money” (Sugar Hill)

- Chapter III, “Real Rocking Groove (Rap & Breaks)” (Grand Groove Records) (1981/1982?)

- Chapter Three, “Smurf Trek” (Grand Groove Records)

- Coldcrush Brothers, “Weekend” (Elite Records)

- Count Coolout, “Touch the Rock (Rhythm Rap Rock Revival)” (Boss Records)

- Crash Crew, “Breaking Bells (Take Me to the Mardi Gras)” (Sugar Hill) (1982/1983?)

- Disco Four, “Whip Rap” (Profile)

- Extra T’s, “E. T. Boogie” (Sunnyview)

- Fab 5 Freddy, “Change the Beat” (Celluloid) (1982/1983?)

- Fearless Four, “It’s Magic” (Enjoy Records)

- Funky Four, “Do You Want to Rock (Before I Let Go)” (Sugar Hill)

- Futura 2000, “The Escapades of Futura 2000” (Celluloid) (1982/1983?)

- Grand Master Flash & the Furious Five, “Scorpio” (Sugar Hill)

- Grand Mixer D.st & the Infinity Rappers, “The Grand Mixer Cuts It Up” (Celluloid)

- Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five Feat. Melle Mel & Duke Bootee, “The Message” (Sugar Hill)

- Jimmy Spicer, “The Bubble Bunch” (Mercury)

- The Jonzun Crew, “Pak Man (Look Out for the OVC)” (Boston International Records)

- Just Four, “Jam to Remember” (Grand Groove)

- Kool D. J. A. J., “Ah, That’s the Joint” (White Diamond Records)

- Kool Kyle (The Original Star Child), “Getting Over” (Frills Records)

- Kurtis Blow, “Daydreamin’” (Mercury)

- M.C. Chocolate Star, “The Pop” (Chocolate Star Records)

- Malcolm McLaren and The World Famous Supreme Team, “Buffalo Gals” (Island)

- Man Parrish, “Hip Hop, Be Bop” (Importe/12)

- Masterdon Committee, “Gonna’ Get You Hot” (Enjoy Records)

- Melle Mel & Duke Bootee, “Message II (Survival)” (Sugar Hill)

- Missy Dee & The Melody Crew, “Missy Missy Dee” (Universal Record Co.)

- Mr. Sweety “G”, “We Want to Get Down” (Mike & Dave Records)

- Nairobi and the Awesome Foursome, “Funky Soul Makossa” (Streetwise)

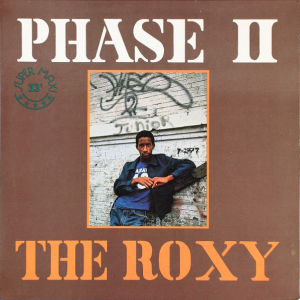

- Phase II, “The Roxy” (Celluloid)

- Pieces of a Dream, “Mt. Airy Groove (Rap Version)” (Elektra)

- Poor Boy Rappers, “The D.J. Rap” (Raina) (1982/1983?)

- Pressure Drop, “Rock the House (You’ll Never Be)” (Tommy Boy)

- Rappers Rapp Group, “Rappers Rapp Theme” (Rappers Rapp Disco Co.)

- Rockers Revenge, “Sunshine, Partytime (Rap)” (Streetwise)

- Star Quality & Class, “Betcha Got a Dude on the Side” (R&R Records)

- Super 3, “When You’re Standing on the Top” (Street Beat Records Inc.)

- Sylvia, “It’s Good to Be the Queen” (Sugar Hill)

- The Disco Four, “Country Rock and Rap” (Enjoy Records)

- The Fearless Four, “Rockin’ It” (Enjoy Records)

- The Masterdon Committee, “Funkbox Party” (Enjoy Records) (1982/1983?)

- The Micronawts, “Smurph Across the Surf” (Tuff City)

- The Packman, “I’m the Packman (Eat Everything I Can)” (Enjoy Records)

- The SD’s Featuring Sherry Richard, “Watch the Clock” (J.B.’s Records) (1982?)

- Treacherous Three, “Yes We Can-Can” (Sugar Hill)

- Wayne & Charlie (The Rapping Dummy), “Check It Out” (Sugar Hill)

- Wham!, “Wham Rap!” (Innervision Records)

- Whodini, “Magic’s Wand” (Jive)

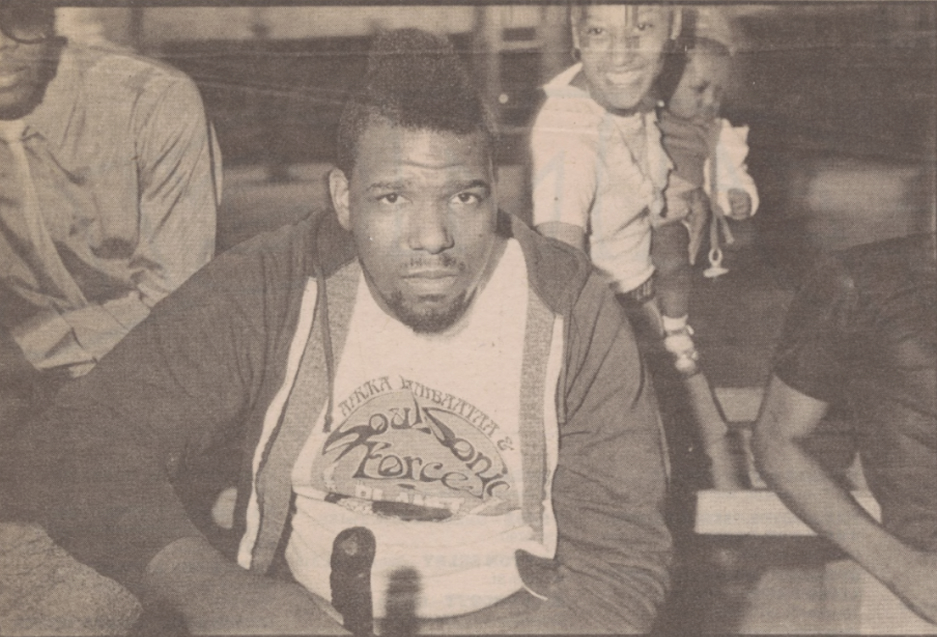

Afrika Bambaataa photo in featured section by Paul Natkin/Getty Images.

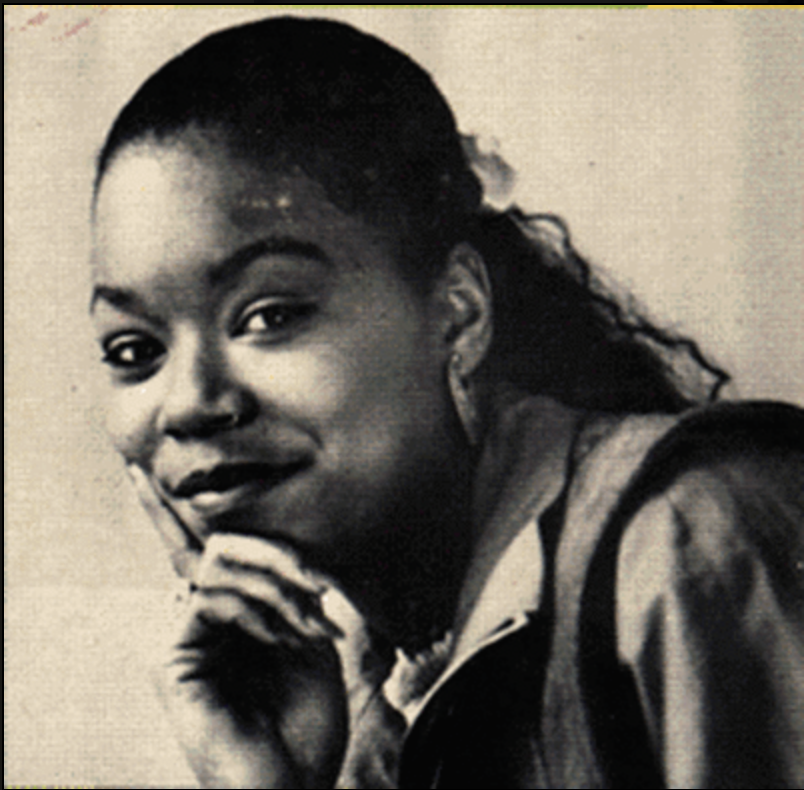

Afrika Bambaataa photo by Sylvia Plachy/Village Voice.

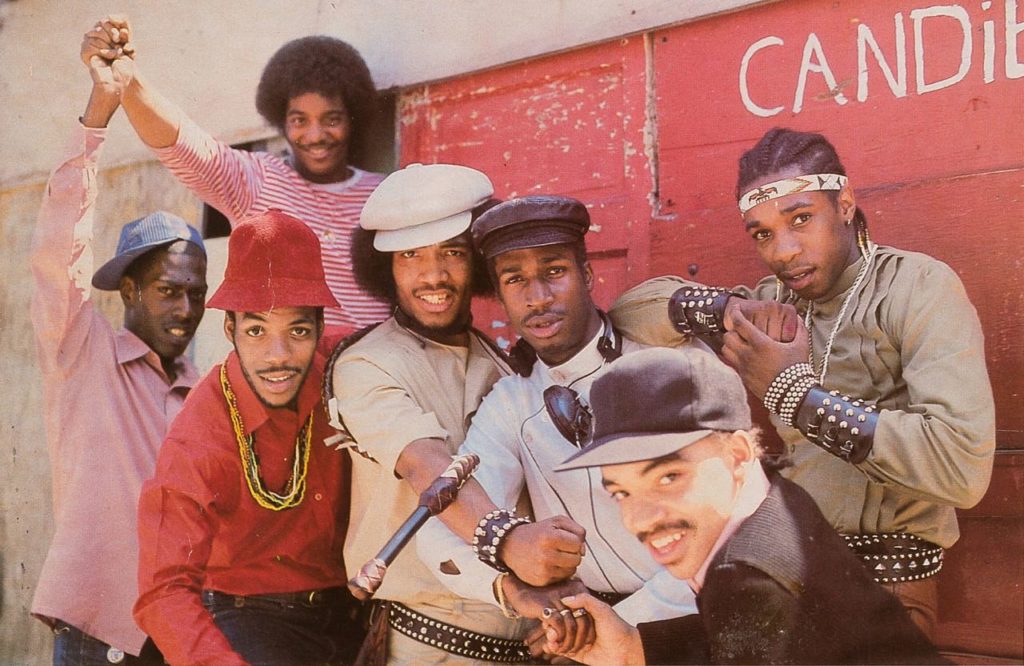

Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five album artwork from The Message by Hemu Aggarwal. Left to right: E-Z Mike, Cowboy, Raheim, Melle Mel, Grandmaster Flash, Kidd Creole, Scorpio.

Vinyl label images taken from Discogs.

Read More: The Best Rap Singles: Former Entries

This post has been updated.

Humthrush.com will always be free to read and enjoy. If you like my work, leave a tip at Ko-fi.com/humthrush.